ONE UP ON SPRING: Hanging ornaments offer this small tree a jump-start on the rapidly approaching season of blossoms. Nearby forsythia bushes are already trying to get their early spring colors going, egged on by mild days and hopes that no late freezes step in as a bud-kill. (Photo by Jack Reynolds)

In my lifelong pursuit of the weird, very few finds are weird to high heavens.Such is the case with a news story out of Israel that might qualify it as biblically weird.

I’ll jump into things by offering some worldwide headlines, like “Scientists have taught goldfish how to drive” (NPR); “Israeli scientists teach goldfish to drive a robotic car on land” (NBC News); “Challenging at first: Scientists teach goldfish how to drive a ‘fish-operated vehicle’” (USA Today).

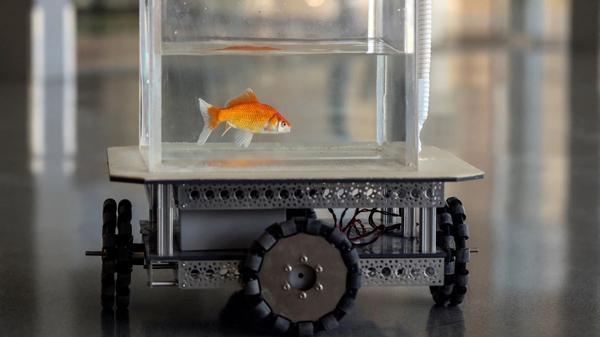

In a nutshell, researchers at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev placed a goldfish bowl atop a special high-tech mobile table – computerized to roll in response to the movements of a goldfish within the bowl. The table followed the swimming fish’s leads.

The fish was then somehow educated to the fact there were some tasty vittles in a dispensing device across the room. All the fish needed to do was “drive” the table over to it by using a series of directive body motions. Once the fish successfully drove up to what amounted to a takeout window, goodies were automatically dropped into the bowl.

Researchers discovered a rookie goldfish driver first went through fully expected trial-and-error steer-abouts, going every which way, though always keeping a fond eye on the food dispenser.

On average, it took a goldfish about 10 failed cruises before it caught onto the concept of aiming its entire swimming essence toward the goodies. One successful drive and it became a walk in the watery park.

After successful drives – and getting filled to the gills – a satiated goldfish might then take a leisurely drive around the room, blowing some friendly bubbles toward all the scientists victoriously smiling from behind a big lab window. Goldfish are very nice that way.

An article in The Scientist Magazine offers “A ‘fish on wheels’ interface allows fish to control a robotic car over land – essentially, a clear tank on a four-wheel platform that moves according to the orientation and movements of the fish inside. It tests whether a goldfish can perceive and understand a waterless environment and transfer their spatial representation and navigation skills to the terrestrial realm.”

I translate that to mean it’s like a fish out of water yet fully immersed. If that doesn’t qualify as profoundly weird …

As to the deeper “But why!?” behind the experiment, it’s probably best to let the deeper significance go unquestioned, but not discounting the possibility of a bored scientist suggesting to colleagues, “Hey, it’s Wednesday. Let’s teach a goldfish to drive,” a suggestion first met with incredulous stares, but quickly followed with a resounding “Let’s go for it, dude!”

As to teaching your pet oscar to drive its 55-gallon tank around the living room, you might want to watch the complexities of the Israeli experiment at www.youtube.com/watch?v=cOb–M5pi6Y.

On a more introspective note, this is further proof that so many back-burnered creatures are way smarter than we think. I’m now convinced many fish are capable of driving better than more than a few summer LBI motorists.

Also, I’m amazed at how well a fish can see the outside world from within its tank. I see through videos that the food-dispensing target points in the experiments were fairly afar. There was no huge neon blue “Food!” sign flashing above. Which gets me wondering. Imagine a future experiment using just such a flashing sign but with the neon word “Cat!” above. Who wouldn’t be floored if the goldfish began frantically driving their tables into the wall at the opposite side of the room?

“Those are some seriously smart goldfish, Moshi.”

SKEETER BEATERS: On a weirdness roll here, I’m itching to talk about mosquitoes. (Piss-poor pun, I know.)

Down Florida way, the people of Key Haven are in line to have roughly a billion farmed mosquito eggs hand delivered to their fairly exclusive cay. It’s all being done in efforts to wipe out a deadly species, the Aedus aegypti, aka the yellow fever mosquito.

A ton of moons back, I wrote about an ongoing effort to genetically engineer mosquitoes that would lay eggs hosting a “self-limiting gene,” which prevents offspring from surviving to adulthood. The utilization of a doomsday protein takes GE/GMO research into deadlyish territory.

The GE mosquitoes in Key Haven have been perfected by a British firm called Oxitec. It describes itself as “the leading developer of biological solutions to control pests that transmit disease, destroy crops and harm livestock.” In a fit of British humor, it has trademarked its skeeter product as Oxitec’s Friendly™ Mosquito. Good one, eh?

The company has achieved the U.S. EPA’s seal of approval. That approval “allows Oxitec to carry out demonstration projects with its safe, environmentally sustainable Aedes aegypti technology designed to control the mosquito that transmits dengue, Zika, chikungunya and yellow fever.”

Oxitec is already field testing its “assortment of manufactured insects” in Brazil, Panama, the Cayman Islands and Malaysia.

Going after mosquitoes is taking on the worst of the worst. Mosquitoes are the deadliest creatures in the entire animal kingdom, killing more than 700,000 people every year.

To its eco-credit, a principal Oxitec aim is to ween mankind from a dangerous dependence on chemical insecticides.

“Our aim is to empower governments and communities of all sizes to effectively and sustainably control these disease-spreading mosquitoes without harmful impact on the environment and without complex, costly operations. The potential for our technology to do so is unmatched, and this EPA approval will allow us to take the first steps towards making it available in the U.S.,” said Grey Frandsen, Oxitec’s CEO.

Not that there isn’t push-back from Florida residents, some seeing the ongoing release, formally known as an uncaged field trial, as a form of “biological terrorism.”

“When something new and revolutionary comes along, the immediate reaction of a lot of people is to say: ‘Wait,’” says Anthony James, a molecular biologist specializing in GE mosquitoes. “So, the fact that (Oxitec) was able to get the trial on the ground in the United States is a big deal.”

As to any trickle-up effects of this experiment, it is feared global warming is urging the yellow fever mosquito our way. Not that we don’t have our own issues with tiger mosquitoes, an invasive species that might eventually demand a GE treatment or two.

By the by, the treatment must be repeatedly administered.

The current batch of Oxitec doomsday eggs impacts only Aedes aegypti. No other mosquito species, of which there are many, are impacted. That leads into the ominously circling question regarding any ecological danger from removing any insect that is foodstuff for other creatures, most notably bats, along with sundry birds and dragonflies. That is where other mosquito species fly in. The targeted yellow fever mosquito is not a “keystone” species. It is theorized its disappearance would have little, if any, negative ecological effect.

I can’t summarily pan the concept of using GE creativity to possibly take a bite out of a disease-carrying bloodsucker. At the same time, I’m among those who will never forget the DDT debacle. Returning to poor punning: Once bitten, twice shy. I’ll watch the egging on of GE mosquito methodologies with keen interest, especially if it can be applied to both deadly and invasive species.

GOING BATTY: I took some time during last weekend’s glorious bout of late-winter mildness to watch the first bats come out of hibernation. Since they’re warm-blooded, they can nimbly take flight if a warm-up so much as hints that flying bugs might be a-flit.

It’s worth stating the obvious: Bat spotting is not an easy look-see. These winged mammals fly by the seats of their pants. Any initial flight plans get thrown out the cave window. They haphazardly fly in any and all available directions, enhancing their in-flight chances of crossing paths with airborne insects, which are often just as lacking in itineraryness.

Famously helping a bat’s bug-finding flights is its ultrasound echolocation, an ultimate form of sonar.

Per howstuffworks.com, a bat emits a sound, then readies its ears for any aberrant echo return, indicating something is within its sound zone. “The bat can also determine where the object is, how big it is and in what direction it is moving. The bat can tell if an insect is to the right or left by comparing when the sound reaches its right ear to when the sound reaches its left ear: If the sound of the echo reaches the right ear before it reaches the left ear, the insect is obviously to the right,” explains the website.

Though some American bat species populations are faltering due to disease and yet-to-be-determined sources of attrition, they still make up a quarter of all mammal species on the planet. Sporting 1,300 species, they comprise the second most common group of mammals after rodents.

A commonly held misconception portrays bats as little more than flying rodents. Not even remotely so. Despite the striking facial resemblance to mice and such, bats are more closely related to primates, per folks who classify creatures. To get a better read on that primate connection, I’ll have to grab me a passing taxonomist.

To the primate good, bats greatly outlive rodents. Rats and friends are lucky to squeeze two or three years out of life, while a run-of-the-sky bat can easily celebrate a 35th birthday “For he’s a jolly good, uh …”

As noted, the calls of cruising bats are ultrasonic, a human-centric term for sounds we can’t hear, which might beg the metaphysical question “If a bat screams in the forest and there’s nobody with ultrasonic hearing around …” But that might soon be answered.

I’m more excited than the next guy over the first bat-call translating devices to reach the common market. Incorporating hitherto unknown technology, possibly gleaned from alien technology, these handheld, highly computerized gadgets offer the first known listen-ins on bats above.

An upper-end bat detector offers an earful of battiness and other pertinent data. According to bats.org.uk, “Individual bat species emit calls with specific characteristics related to their size, flight behavior, environment, and prey types. This means that with the aid of bat detectors we can identify many species by listening to their calls or recording them for sound analysis on a computer.”

There is one bat-s–t crazy side to bat detectors. A good one, with bat frequency scanning capacities, a digital readout and a recording capacity, doesn’t come cheaply. For example, I pointlessly covet the Full spectrum/Direct Sampling Demo Pettersson D1000x s/n 282, on sale for $3,495. There is a slew of lower-cost “heterodyne” models, in the $400 range. Many require tediously hand turning a knob to locate a “working” bat frequency.

I’m currently targeting a feasibly priced smartphone bat detector attachment that can fly with the best of them.

RUNDOWN: The Recreational Fishing Alliance publication “Making Waves Spring Edition 2022” has a fascinating segment titled “Striped Bass and Satellites.” Check it out at ssuu.com/recreationalfishingalliance/docs/making_waves_spring_edition_2022/s/15175520.

What jumps out at me is the graphics showing the meandering of sponsored stripers outfitted with transmitters, which come off with time.

Along with ramblings far beyond what one might expect from a fish envisioned as holding in place for long periods of time is the thoroughly stunning “ping” proof that the beloved N.J. gamefish move far out to sea, talking in canyon terms.

Are such swings into the open ocean something new, or have stripers always gone sightseeing out there? Since bass can’t be kept in federal (EEZ) waters, there has never been much anecdotal accounting of their lives and times once they’re beyond state waters.

Overall, this data could be a game changer for those who write the natural history books on bass. I’m sure there will be those pointing to climate change.

Closer in, I have gotten word of good to downright excellent spring bassing, with Graveling Point already offering keepers at a regular clip. Go bloodworms! The Island’s bayside bass action is there … then not so much. I’m in that user group, using plugs and jigs after dark/work. By the by, I no longer keep any bass, yet I encourage folks to take their allotted keepers. It’s complicated – plus I prefer bluefish.

Winter flounder fishing pressure is light, with most boat anglers seeking them in the name of maintaining a “spring tradition.” Two allowable keepers of 12 inches and up can still make for a decent total boat take.

Perching is picking up, but nothing to alert the media over.

jaymann@thesandpaper.net